The Dean of the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia, Bob Pianta, recently did an interview with the radio show/podcast "With Good Reason." He says he can identify whether or not a teacher is a good teacher quickly, regardless of content.

Carry on, I'm just over here taking notes...

Listen to it here!

Thursday, June 27, 2013

Those Who Can...Teach

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

Tech-Out with ELLs

A look at: "The Effects of Multimedia-Enhanced Instruction on the Vocabulary of English-Language Learners and Non-English-Language Learners in Pre-Kindergarten Through Second Grade," by Rebecca Silverman and Sara Hines.

When I initially began reading this article, a red flag flew up. I know the research shows that people cannot learn language from a video, even if that video is interacting with them (like through a video chatting service), so I did not understand why this article would review that research area. Upon further reading, I saw that Silverman and Hines clarified that they were seeking to augment good vocabulary instruction with multimedia, rather than trying to teach language (and the social queues that come with it) through video alone. It appears as if some forms of multimedia vocabulary supplementation can be helpful for today's ELLs, which can be somewhat convenient for some teachers. Watching a Sesame Street segment could be a temporary station in a classroom full of students learning through many means.

When I initially began reading this article, a red flag flew up. I know the research shows that people cannot learn language from a video, even if that video is interacting with them (like through a video chatting service), so I did not understand why this article would review that research area. Upon further reading, I saw that Silverman and Hines clarified that they were seeking to augment good vocabulary instruction with multimedia, rather than trying to teach language (and the social queues that come with it) through video alone. It appears as if some forms of multimedia vocabulary supplementation can be helpful for today's ELLs, which can be somewhat convenient for some teachers. Watching a Sesame Street segment could be a temporary station in a classroom full of students learning through many means.

To Group Vocab Words or Not...

A look at: "Effects on vocabulary acquisition of presenting new words in semantic sets versus semantically unrelated sets" By Ismail Hakkı Erten and Mustafa Tekin

The conclusion of this article surprised me, but only because it differed with what I remember about the first few years of L2 instruction. The writers conclude that new words should not be presented in semantic sets because it confuses the learner. Rather, they should be presented in unrelated sets of words, so the learner's limited short term memory can concentrate on the new words as individuals instead of trying to remember the differences between them. Again, this was a surprising conclusion, only because I can remember so many vocab lists that contained similar words. I suppose the teacher thought it would be best to show us these similar words together so as not to be confused, but I see now that it was counterproductive.

The conclusion of this article surprised me, but only because it differed with what I remember about the first few years of L2 instruction. The writers conclude that new words should not be presented in semantic sets because it confuses the learner. Rather, they should be presented in unrelated sets of words, so the learner's limited short term memory can concentrate on the new words as individuals instead of trying to remember the differences between them. Again, this was a surprising conclusion, only because I can remember so many vocab lists that contained similar words. I suppose the teacher thought it would be best to show us these similar words together so as not to be confused, but I see now that it was counterproductive.

Languages and Children: Chapter 9

This chapter shows how much cultural emphasis can be a vehicle for implicitly learning a language, as well as the greatest motivation to learn it. I love the idea of starting with a culturally integrative lesson to help teach vocabulary and language. As Curtain and Dahlberg allude, it can help bridge a gap that ELLs might fear crossing: knowing more about the country in which they now live. The Classroom Exchanges idea jumped out as particularly interesting as I suspect it would get the adrenaline pumping in the veins of these young learners: a great recipe for learning success. I also love the ideas that integrate technology and uniting students with other students around the globe.

Languages and Children: Chapter 3

This chapter gives an overview of three kinds of communication: interpersonal, interpretive, and presentational. I love that it gives concrete examples and suggestions for teachers to use in their classroom, beginning with stepping stone activities. As we have discussed in class, it is most important that we help students build a bank of meaningful and useful vocabulary in order for them to partake in these three kinds of communication. My brain wants me to organize these three in my mind as if they were three steps in a process, though Curtain and Dahlberg emphasize the holistic nature of communication. Again, I will visit this chapter again to sample some of the activities they provide.

ACCESS-ible Testing?

Upon looking at and reflecting on the WIDA ACCESS test, I'm not satisfied with how we choose to assess our students, but I cannot offer a better alternative at the moment. I've witnessed the MAPS testing in the Charlottesville City Schools for a group of WIDA level 2.5 and below students. What I noticed with that testing and with the ACCESS test is that students are given zero scaffolding aid when taking the test. Just like with the reading fluency tests for non-ELLs, the proctors are required to push the students until they reach their frustration level. I suggest that the nature of these tests and the sharp jolt in difference between their daily experience with assessments and how this test assesses them will be the source of more frustration. Therefore, how accurate could the results be? Again, I can only whine about this without presenting an alternative solution to what I know is a necessity.

Making it Happen: Chapter 5

Discovering the purposeful difference between implicit and explicit teaching was revolutionary in my learning as a preservice teacher last fall. I knew I learned better (and that the learning "stuck") through implicit teaching over explicit teaching, but most of my memories of elementary school learning was in an explicit teaching setting. This chapter reviews the different methods for teaching and shares that current research does not draw a distinct conclusion between implicit and explicit instruction for L2 learners. Overall, it's important for the teacher to reflect on how the student learns best; they can be product oriented or process-oriented. I will revisit this chapter many times for the strategies for listening, speaking, reading, and writing.

Making it Happen: Chapter 8

The concept of integrating physical involvement in the language learning process is one that will take me some time to add to my own bag of tricks. For whatever reason, I'm stuck in this idea that the only way to get through all of the content I need to teach is through direct instruction (even though I know how inaffective nonstop direct instruction can be). It's exciting to me to have this chapter's resources at hand. My favorite ones that Richard-Amato shared are the activities, though I know the simple commands are great first steps for ELLs. I'm grateful Richard-Amato also shared information about the limitations of TPR and expansions on the concept through storytelling and the audio-motor unit. This is where the rubber meets the road.

Input to Output: Chapter 5

"Does the first language cause interference?" The biggest question in my mind at this time and the first one VanPatten answers in his FAQ chapter. As is the case with most academic answers, he explains that "yes and no," the first language can be a crutch, but that we all go through the same process to learn our second language, no matter what. The big question, though, is also hard to completely answer through research as it is "slippery" to test how much of the L1 transfers to aid in learning the L2.

We spoke about the second question, "What about the use of the first language in the classroom?" in class. It's a balance and, of course, social implications must be examined.

This is one concept behind language acquisition that is most fascinating to me: "It is possible, then, that the differences we see between L1 and L2 acquisition are also attributable to external factors and not to internal processes." How much of our perspective (cultural and linguistic) plays a role in our ability to become proficient in an L2?

I've often operated under the assumption that non-romance languages would be harder for me to learn, considering English has some romance language influence. It was humbling to realize and accept that, "Every language has some things that kids get right away and other things that even school-aged kids mess up, but as a whole no language can be considered easier or harder."

Obviously, I have not been succinct, but these were my favorite parts of the chapter.

We spoke about the second question, "What about the use of the first language in the classroom?" in class. It's a balance and, of course, social implications must be examined.

This is one concept behind language acquisition that is most fascinating to me: "It is possible, then, that the differences we see between L1 and L2 acquisition are also attributable to external factors and not to internal processes." How much of our perspective (cultural and linguistic) plays a role in our ability to become proficient in an L2?

I've often operated under the assumption that non-romance languages would be harder for me to learn, considering English has some romance language influence. It was humbling to realize and accept that, "Every language has some things that kids get right away and other things that even school-aged kids mess up, but as a whole no language can be considered easier or harder."

Obviously, I have not been succinct, but these were my favorite parts of the chapter.

Tuesday, June 25, 2013

Input to Output: Epilogue

[caption id="attachment_67" align="alignright" width="240"] Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]

Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]

I'm so happy to read that, as a member of a confused generation of students taught through inconsistent philosophies about the need for phonics over meaning-based over reading-intensive, there seems to be more consensus for the next generation. This text agrees with the other research-based texts I've read that scream from the rooftops that we must be teaching meaning-based lessons, not just decoding. We must also strike a balance between our methods.

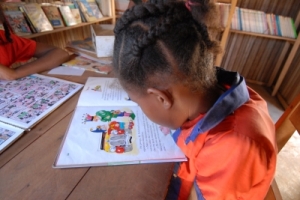

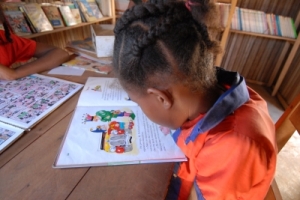

This book also makes me want to start a program for story book reading at local fast food restaurants (because they are hubs) in highly ELL-populated areas, so that these students and their parents get as much interaction as possible in the desired L2 of English. These in-class model examples are useful!

Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]

Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]I'm so happy to read that, as a member of a confused generation of students taught through inconsistent philosophies about the need for phonics over meaning-based over reading-intensive, there seems to be more consensus for the next generation. This text agrees with the other research-based texts I've read that scream from the rooftops that we must be teaching meaning-based lessons, not just decoding. We must also strike a balance between our methods.

This book also makes me want to start a program for story book reading at local fast food restaurants (because they are hubs) in highly ELL-populated areas, so that these students and their parents get as much interaction as possible in the desired L2 of English. These in-class model examples are useful!

Input to Output: Chapter 4

[caption id="attachment_59" align="alignright" width="240"] Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]

Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]

It's helpful to note that "output," like "input," only refers to communicative, meaning-bearing output in the field of SLA. Output processing refers to "access" and "production strategies." Good grief, the brain does some amazing things. Somehow it stores the idea of an object, the word (or lemma) for the object, the grammar surrounding all that involves the object that the user wishes to communicate, and then it tells the motor cortex what and how to communicate it.

The brain "fills in the gaps" whenever necessary (especially when learning an L2), or, uses a "communication strategy" if they cannot access the proper steps in the hierarchy. The trickiest and most profound (yet simple) part of all of this is that I'm learning about language through language and then communicating (producing output) through language. My declarative knowledge about English led me to develop procedural knowledge enough to read and communicate somewhat intelligently. Phew.

Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]

Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]It's helpful to note that "output," like "input," only refers to communicative, meaning-bearing output in the field of SLA. Output processing refers to "access" and "production strategies." Good grief, the brain does some amazing things. Somehow it stores the idea of an object, the word (or lemma) for the object, the grammar surrounding all that involves the object that the user wishes to communicate, and then it tells the motor cortex what and how to communicate it.

The brain "fills in the gaps" whenever necessary (especially when learning an L2), or, uses a "communication strategy" if they cannot access the proper steps in the hierarchy. The trickiest and most profound (yet simple) part of all of this is that I'm learning about language through language and then communicating (producing output) through language. My declarative knowledge about English led me to develop procedural knowledge enough to read and communicate somewhat intelligently. Phew.

Making it Happen: Chapter 3

It's so interesting to read about the cognitive differences (and similarities) involved in learning a first language and learning a second language. There are obvious reasons why the situations will differ between learning L1 and L2, such as time, developmental maturity, and experiences.

[caption id="attachment_57" align="alignright" width="240"]![Image courtesy of [image creator name] / FreeDigitalPhotos.net](http://teachingseconds.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/id-1009182.jpg?w=300) Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]The most poignant part of this chapter helped to quench a thirst for an answer I asked my dad when I was 10: how can we learn a second language unless our brains just have their own language? In other words, I thought the only way we could know one language was because our "brain language" learned how to translate from "brain language" to "L1" and then again for "L2."

Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]The most poignant part of this chapter helped to quench a thirst for an answer I asked my dad when I was 10: how can we learn a second language unless our brains just have their own language? In other words, I thought the only way we could know one language was because our "brain language" learned how to translate from "brain language" to "L1" and then again for "L2."

This chapter (obviously) strays from that rudimentary, 10-year-old-thought-process, because, as it shows, learning a language is so different from learning other concepts or content. It was good to read, once again, of Vygotsky's and Piaget's eternal impact on the field of education in this chapter.

[caption id="attachment_57" align="alignright" width="240"]

![Image courtesy of [image creator name] / FreeDigitalPhotos.net](http://teachingseconds.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/id-1009182.jpg?w=300) Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]The most poignant part of this chapter helped to quench a thirst for an answer I asked my dad when I was 10: how can we learn a second language unless our brains just have their own language? In other words, I thought the only way we could know one language was because our "brain language" learned how to translate from "brain language" to "L1" and then again for "L2."

Image courtesy of FreeDigitalPhotos.net[/caption]The most poignant part of this chapter helped to quench a thirst for an answer I asked my dad when I was 10: how can we learn a second language unless our brains just have their own language? In other words, I thought the only way we could know one language was because our "brain language" learned how to translate from "brain language" to "L1" and then again for "L2."This chapter (obviously) strays from that rudimentary, 10-year-old-thought-process, because, as it shows, learning a language is so different from learning other concepts or content. It was good to read, once again, of Vygotsky's and Piaget's eternal impact on the field of education in this chapter.

Input to Output: Chapter 3

This chapter was quite full, a good bridge from the two chapters preceding. This one went much deeper into the network and connection-making that our brains have mastered as speakers of language. There are so many rules about syntax within the English language native speakers don't know that they know. I can recall a teacher instructing us about a certain grammatical rule saying, "You'll just know it's wrong when you hear it." Obviously, that's not going to fly in a room with non-native speakers.

This chapter also goes into the differences and implications of accommodation and restructuring with regard to the development in the linguistic system. Accommodation and restructuring through instruction bring about change.

This chapter also goes into the differences and implications of accommodation and restructuring with regard to the development in the linguistic system. Accommodation and restructuring through instruction bring about change.

Welcome!

Thank you for joining me on the path of learning more about learning! Language has always been a fascinating concept to grasp. I've taken a few classes in undergrad that cater to this passion, but now I'm finally learning more about the methods involved in learning a language and why our brains react to this process the way that they do!

This blog is starting out as an assignment for EDIS 5480 at the University of Virginia -- an ELL methods overview course. However, as my time spent working with ELL students this year has been so rewarding, I suspect I will have many real world stories and contributions I can make once I begin my career as a teacher.

Here we go!

This blog is starting out as an assignment for EDIS 5480 at the University of Virginia -- an ELL methods overview course. However, as my time spent working with ELL students this year has been so rewarding, I suspect I will have many real world stories and contributions I can make once I begin my career as a teacher.

Here we go!

Input to Output: Chapter 2

Once again, I came into reading this chapter with a mindset that the chapter's focus on "input" would be somewhat simple, knowing that this is a general overview of SLA. I'm humbled again as this is not an easy concept to grasp upon diving deeper. During my reading, I asked one of the questions in upper right hand corner out loud to myself: "How do learners get linguistic data from the input?" Ask a child this question and they might come up with the same initial answer I thought: they just do. VanPatten points out how different it is to learn a language than it is to learn anything else because when one learns how to count or about the batting average of their favorite baseball player, they do so through language. Learning how to make connections between what are really arbitrary symbols, sounds, words, and data is just a tiny bit of what makes learning a language so challenging and different than learning other content.

From Input to Output: Chapter 1

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="234"] Image from FreeDigitalImages.net[/caption]

Image from FreeDigitalImages.net[/caption]

This chapter helped answer a lot of the general questions I had about SLA and bring new questions to the surface. I trust VanPatten will answer these new ones in the future. I did not realize that SLA was such a young field, though I should have known, as the academic world has only recently made efforts to avoid xenocentrism and to reflect on culture from many perspectives. Of course, as VanPatten admitted, the five "givens" really are simple on the surface and are ones we could have identified in class. However, it was interesting to read VanPatten's reflection on the details behind these "givens." We, as those who could have so wisely discovered these five on our own, only accept them as "givens" because learning our first language was so natural. We recognize these "givens" because of the work that we have already done to learn our initial language (and perhaps a second).

Image from FreeDigitalImages.net[/caption]

Image from FreeDigitalImages.net[/caption]This chapter helped answer a lot of the general questions I had about SLA and bring new questions to the surface. I trust VanPatten will answer these new ones in the future. I did not realize that SLA was such a young field, though I should have known, as the academic world has only recently made efforts to avoid xenocentrism and to reflect on culture from many perspectives. Of course, as VanPatten admitted, the five "givens" really are simple on the surface and are ones we could have identified in class. However, it was interesting to read VanPatten's reflection on the details behind these "givens." We, as those who could have so wisely discovered these five on our own, only accept them as "givens" because learning our first language was so natural. We recognize these "givens" because of the work that we have already done to learn our initial language (and perhaps a second).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)